Presence

journal

special issue on Virtual Heritage

MIT Press

15.3, June 2006

Aspen the Verb: Musings on Heritage and Virtuality

Michael Naimark

Abstract

Aspen, the picturesque mountain town in Colorado,

is known for two processes, or "verbs," relating to heritage and

virtuality. One is to "moviemap," the process of rigorously filming

path and turn sequences to simulate interactive travel and to use

as a spatial interface for a multimedia database. The other is to

"Aspenize," the process by which a fragile cultural ecosystem is

disrupted by tourism and growth. This essay reflects on their significance

and describes exemplar work integrating these two seemingly disparate

concepts."

Introduction

It's July, 2003, and I'm back in Aspen. Actually

not in town, but in Missouri Heights just above El Jebel, the small

town a half-hour drive "down-valley" from Aspen, at my sister Judy

and her family's home. Judy is a local, having visited Aspen in

the early 1970s and stayed. Like many of her friends who also stayed,

she eventually married, had children, and moved down-valley. Real

estate ads in this week's Aspen Times list Aspen homes beginning

at $2 million and going upwards of $10 million.

My first time in Aspen was 25 years ago, filming,

of sorts. Several pulse-frame motion picture cameras were configured

panoramically on top of a jeep and triggered by a fifth wheel trailing

from the rear. We were filming one frame every ten feet, driving

up and down every street in town and through every intersection

every possible way.

That Judy lived in Aspen then was roughly Reason

Number Four why a small group of MIT researchers, myself included,

chose Aspen, Colorado, as the test bed for a new form of interactive

experience. Judy worked at "Aspen State Teacher's College," not

a college at all but a local prank and small business selling t-shirts,

mugs, and other college paraphernalia to tourists, mostly skiers

and hikers. Judy's local knowledge would be useful for production,

it was concluded. The other two reasons were that Robert Mohl, another

MIT researcher, grew up in Colorado and had professional photography

experience around Aspen; and that the nascent Aspen Design Conference

would be a befitting venue for presenting the project when it was

completed.

Whoops, did I forget Reason Number One? Simply

- because it was Aspen, a intensely beautiful mountain town with

a single traffic light and a lively local community. Why fib? Aspen

was a cool place and we all wanted to go.

The Aspen Moviemap - Place Representation

The Aspen Moviemap was the first interactive

"virtual travel" project to incorporate photo-realistic images via

computer-controlled videodisc. The project, which began in 1978,

originated at MIT's Architecture Machine Group, Nicholas Negroponte's

proto Media Lab. Andrew Lippman, already a long-time colleague of

Nicholas', was the Principal Investigator. Funding came from DARPA's

Cybernetics Technology Office, headed at the time by Craig Fields,

who had already supported other projects relating to visual mapping.

The Aspen Moviemap was an academic, non-commercial, non-classified

project.

"Its goal was to create so immersive and realistic

a 'first visit' that newcomers would literally feel at home, or

that they had been there before," recalls Andy Lippman. "DARPA realized

the need after Israeli soldiers practiced for the recovery of an

airplane hijacked to Entebbe by using an abandoned airfield made

up to look similar" (Lippman, 2004)

The optical videodisc was a revolutionary technology

then. Remember, if you can, 1978: 16mm film was the primary medium

for all television news gathering; video editing was barely computerized;

and storing moving pictures in computer memory was ten years away.

The optical videodisc was capable of storing a half-hour of analog

video (54,000 frames) and two-channel audio, with instant access

to all the material via computer control. In early 1978, "ArcMac"

received one of the first twenty-five prototype videodisc players

from the MCA Corporation, and with it a contract to master three

discs of its own.

That Spring, an energetic MIT undergraduate named

Peter Clay proposed "mapping" the hallways of MIT by mounting a

16mm film camera capable of shooting single frames on a dolly tripod,

then wheeling it down the hallways triggering one frame every step

he took. With the help of graduate students Bob Mohl and me, Peter

shot the hallways. The footage was included on the "B-side" of the

"Slidathon" disc, MIT's first laserdisc. Peter and Bob made a simple

computer program that allowed control of speed and direction moving

up and down the hallways. Voila! "Virtual travel."

That Fall, then again in the Winter, a small

squadron from MIT descended upon Aspen to make a "sweep," under

the general direction of Nicholas, Andy, and Craig. The camera rig

on the jeep was designed and operated by wildlife cinematographer

John Borden, MIT undergraduate student Stan Syzaki, and me. Its

footage was conceived as a backbone on which a comprehensive audiovisual

survey of Aspen could be spatially organized. This survey included

"micro-documentaries" by MIT Film/Video professor Richard Leacock;

binaural sound collected by ArcMac faculty Steve Gregory and graduate

student Rebecca Allen; tens of thousands of still frames, including

of every building facade in town, shot in summer and in winter,

and historical images re-photographed by ArcMac graduate student

Scott Fisher; non-audiovisual data (which we called "data data,"

e.g., cases of beer consumed per week and total number of beds),

collected by ArcMac graduate student Walter Bender; and overview

map ideas by UC Santa Cruz cognitive psychologist Kristina Hooper.

Bob Mohl, who went on to write his PhD dissertation on the Aspen

Moviemap, was everywhere. (Mohl, 1981)

A sweep like this is not inconspicuous - driving

down the center of the streets and photographing every facade -

and the Aspen townspeople were characteristically nonchalant about

our presence. Everyone, from the sheriff's office to store owners

to residents, was cooperative, if not amused.

The final project took shape back at the lab,

where the material was organized, edited, and mastered onto a videodisc.

The controlling software and interface design, with the additional

help of ArcMac graduate students including Steve Yelick, Paul Heckbert,

and Ken Carson, turned the mass of material into a singular virtual

travel experience. By Summer, 1979, the Aspen Moviemap was ready

for its first demo, and it caught the attention of the press.

Figure

1: The Aspen Moviemap experienced in the "Media Room" at the Architecture

Machine Group, MIT, c1980. The "traveler," seated in an instrumented

armchair, controls speed and direction of travel. Touch screens

displaying map and aerial views allow access to additional multimedia

material. (Photo: Bob Mohl)

Moviemapping, it seemed at the time, was destined

to enjoy widespread popularity as a new medium for experiencing

place, for virtual travel and virtual tourism. The dream was that

popular tourist destinations, spectacular landscapes, sacred places,

and heritage sites could be moviemapped and appreciated by many

more people than could actually go there. It would be more experiential

than magazine photographs and linear television shows. Indeed, it

was most often referred to as "surrogate travel."

Several participants from the original Aspen

team went on in various permutations to moviemap Paris for the Paris

Metro (1985), Palenque for the Bank Street College (1985), San Francisco

for the Exploratorium (1987), Karlsruhe Germany for the Center for

Arts and Media (ZKM) (1990), and Banff for the Banff Centre for

the Arts (1993). (Naimark, 1997)

The concept of community "sweeps," often with

the participation of locals and students, continued. In the early

1990s, the Apple Multimedia Lab organized a one-day sweep of Moss

Landing, a small California coastal village. In the mid 1990s, the

UC Berkeley Center for Design Visualization and the UNESCO World

Heritage Centre led groups to sweep various cultural heritage regions

in Europe. New digital technologies for capture, modeling, and display

add greater possibility and practicality to moviemapping.

Moviemap - the verb - made Aspen an exemplar

of what place representation using new media technologies can be.

Aspenization - Place Control

But the verb more popularly associated with Aspen than "to moviemap" describes something else. To "Aspenize," says one longtime Aspen public official, is when small towns "choke on what their charm has brought them." Aspen has become the poster town for this process, and its emblematic image is a mountain landscape foregrounded by an airport full of private jets.

Figure

2: "Traffic jam" of private jets at the Aspen Airport. (Photo: Paul

Conrad, The Aspen Times)

The word "Aspenization" first appeared nationally

in a 1993 Newsweek story about Crested Butte, another picturesque

Colorado mountain town:

A town [Crested Butte] with such attractions

is a natural target for what people in Colorado call Aspenization:

the upscale living death that fossilizes trendy communities from

Long Island's Hamptons to California's Lake Tahoe. Aspen was a splendid

place, too, before it was discovered by the rich and famous -- and

the greedy and entrepreneurial. Now it's a case study in overdevelopment.

Its lavish second homes sit empty for most of the year while three

quarters of the work force, who can't afford to live there, commute

from 40 miles down-valley -- a two-hour trek at rush hour. (Gates,

1993)

In 1998, the New York Times described Aspenization

and housing costs:

Welcome to Aspen, home of the most expensive

residential real estate in the nation. Last year, the typical home

here sold for $1.5 million -- 12 times the national average. ''Doctors

in Aspen are just blue-collar workers,'' said Mallory Harling, an

obstetrician-gynecologist who lives in public housing with his wife,

Karen. ... With ''Aspenization,'' a scare word in the region, the

saga of roaring real estate prices in Rocky Mountain resorts can

best be told in this silver mining town, built over a century ago

at the end of a box canyon, at the top of the Roaring Fork Valley. ... In 1996, a house at the base of Aspen Mountain sold for $9 million.

Last summer, a house atop Red Mountain sold for $19.7 million. This

spring a 67-acre ranch and house just outside town is on the market

for $24.8 million. Real estate agents sniff that $1 million will

buy only a ''fixer-upper.'' Elsewhere in town, rents are on a par

with New York City. ... ''Affordable housing is absolutely fundamental

to our efforts to keep Aspen real,'' said John Bennett, Aspen's

Mayor, who has seen about 70 percent of the city's private housing

become vacation homes. ''We don't want to be just an empty theme

park, full of houses that are occupied only a few weeks out of the

year. We want to remain a real-life town, with living, breathing

people who have real jobs.'' ... Aspen residents joke that their town

is divided into two groups: people with three jobs, and people with

three houses. (Brooke, 1998)

"Aspenization" has since been used to describe

growth and development in towns from Santa Fe to Whistler and from

Hawaii to New Zealand.

For better and for worse, Aspen has earned this

transformation into a verb. The Aspen locals have a long and spicy

history of trying to maintain control of their community. In 1969,

"gonzo" journalist and Aspen local Hunter S. Thompson co-founded

the "Freak Power" party. Its mayoral candidate Joe Edwards ran on

an anti-development platform that included, among other things,

replacing the paved roads with sod to slow down development. Edwards

lost by six votes. The following year Thompson ran for sheriff of

Pitkin County, the much larger region, and lost by 500 votes. If

ever there were "tipping points" in the history of US anti-development

movements, these Aspen elections may have been as close as it came.

But Aspenization isn't simply about being anti-wealth.

Sister Judy: "The rich used to come here and wear flannel shirts

and jeans." Adds Michael Kinsley, Pitkin County Commissioner in

Aspen in the 1970s, "there was an unspoken ethic here that the rich

had to look and act like everyone else. Aspen was one of the few

places where Jack Nicholson or Goldie Hawn could walk down the streets

and nobody cared." (Kinsley, 2003)

Aspenize - the verb - made Aspen an exemplar

of what happens when local custodians lose control of the place.

Representation Equals Control

That Aspen spawned the both Moviemap and Aspenization

is noteworthy for several reasons. First, issues surrounding place

representation, as exemplified by the Moviemap, and issues surrounding

place control, as exemplified by Aspenization, are two of the most

prominent issues surrounding heritage sites. Second, these two professional

communities tend to be of different cultures and rarely interact:

they drink in different bars. Finally, evidence suggests that representation

and control are deeply interconnected.

Consider the work of UC Berkeley Geography Professor

Bernard Nietschmann. His early fieldwork in the 1960s was on the

Caribbean coast of Nicaragua working with the Miskito, Sumo, and

Rama Indians. In the early 1980s, reports of relocation and murder

of coastal Indians by the Sandinistas compelled Nietschmann to see

for himself, and he went in "unofficially." Nietschmann, who at

the time was Chair of the UCB Geography Department, was the first

American in this region during the conflict, and he returned not

shy about taking an aggressive pro-indigenous stance. His 1984 article

in Co-Evolution Quarterly journal, with his ample use of the phrase

"Miskito Indian Warriors," received the highest number of angry

reader responses in the journal's history. CQ assigned another writer

to go to Nicaragua for a second opinion. (Nietschmann, 1984) (Baker,

1985)

Eleven years later, Nietschmann published another

report, in Harvard's Cultural Survival journal, outlining a different

paradigm, of making maps instead of using guns. Using portable Global

Positioning Satellite (GPS) gear, Nietschmann worked with local

Miskito teams to re-map their territory. In 1991, as a direct result,

the Nicaraguan government created a 4,000 square mile Miskito Coast

Protected Area, under the control of the Miskito people. (Nietschmann,

1995)

In the mid-1990s, Nietschmann was invited by

42 Maya villages in southern Belize to help them map their own territory,

to win a Belize Supreme Court battle against corporate land use.

In 1997, the villages collectively authored the "Maya Atlas." The

Atlas has become an important educational and legal instrument,

as well as an aesthetically vibrant "coffee table" book. (Toledo

Maya Cultural Council, 1997)

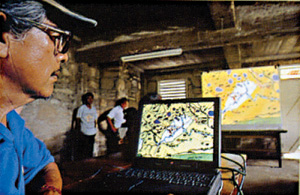

Figure 3: "Media Room" set up for production of the Maya Atlas in

the basement of the church, San Antonio, Belize. (Photo: Bernard

Q. Nietschmann)

Nietschmann summed things up succinctly: "Maps

are power. Either you will map or you will be mapped." (Nietschmann,

1997)

As we move forward with our powerful new tools

for place representation and virtual heritage, the questions remain

"by who?" and "for who?" With travel and tourism representing 10%

of the global economy, there's a lot at stake to get it right. But

it's painfully easy for the outside holders of the technology, rather

than the local providers of the content, to set the rules. Without

balance and cooperation between both, the loss will be everyone's,

particularly ours.

Acknowledgements

A colleague once joked that if everyone who claimed

to have worked on the Aspen Moviemap were to convene for a reunion,

it would have to be held in Denver because Aspen is too small. I

gratefully acknowledge the review and fact-checking of the Moviemap

text by Andy Lippman and Bob Mohl.

I also gratefully acknowledge New York Times

writer Jim Brooke, former

Pitkin County Commissioner Michael Kinsley, and Judy Naimark Sullivan

for their help. I also thank Ed Bastion, Hunter Thompson's Campaign

Manager in 1970, for confirming details directly with Mr. Thompson

for this essay; and Paul Conrad and The Aspen Times for use of the

photograph.

Bernard Nietschmann was a longtime mentor and

personal friend. Once, on a boat with Barney on the Rio San Juan

in Nicaragua, I made the very dumb mistake of referring to our location

as the "middle of nowhere." He blew up at me and screamed "What

is nowhere?!? There is NO nowhere!" Barney, who died in 2000, was

uniquely gifted at bridging cultures.

References

Baker, W. (1985). "Izum in Rindydinkaragua."

Whole Earth Review [formerly CQ], No. 46.

Brooke J. (1998). "Subsidies for High-Income

Families." New York Times, May 17, 1998.

Gates D. (1993). "Chic Comes to Crested Butte."

Newsweek, December 27,1993.

Kinsley M. (2003). Telephone interview, 24 July

2003.

Lippman A. (1980)."Movie-maps: An application of the optical videodisc to computer graphics." ACM Siggraph Proceedings, 1980.

Lippman A. (2004). Personal email, 29 October

2004.

Mohl R. (1981) "Cognitive Space in the Interactive

Movie Map: An Investigation of Spatial Learning in Virtual Environments."

PhD dissertation, Education and Media Technology, M.I.T.

Naimark M. (1997). "A 3D Moviemap and a 3D Panorama."

SPIE, 3012.

Nietschmann, B. Q. (1984). "Nicaragua's Other

War." Co-Evolution Quarterly, No. 41.

Nietschmann, B. Q. (1995). "Defending the Miskito

Reefs with Maps and GPS: Mapping With Sail, Scuba and Satellite."

Cultural Survival Quarterly, Vol. 18, No. 4.

Nietschmann, B. Q. (1997). "The Making of the

Maya Atlas," in Maya Atlas, pp. 136-149, North Atlantic Books,

Berkeley, CA.

Toledo Maya Cultural Council and the Toledo Alcaldes

Association (1997). Maya Atlas. North Atlantic Books, Berkeley,

CA.

|