Cyberarts International

Compendium Prix Ars Electronica

Vienna and New York: Springer, 1998

Interactive Art - Maybe It's a Bad

Idea

Michael Naimark

Interval Research Corporation

1997

We've been hearing about "interactive art" for a good

twenty years now, particularly in the context of computers accessible

to artists. A great many very smart and talented people have worked

very hard exploring its potential. The visionaries have waxed eloquently

about it, the artists have promised us bold new artforms, and the

entrepreneurs have promised us vast new industries.

And what have we seen? Well certainly many interesting things, some

of which are pretty good. But as good as the first two decades of

photography? Of paints in tubes? Of sound recording? Of cinema?

I don't think so.

So I really must wonder: maybe interactive art is a bad idea. At

least in the ways we've been thinking, practicing, and (especially!)

promising it.

When I ponder very carefully how much interactive art I've experienced

that has truly moved me, I can recall four works.

Only four.

And two of the four were made by Czechs (go figure), so let's start

there.

Of all the interactive artforms promised, the "interactive

movie" has undoubdtedly been the most flaunted. The concept

is that the audience can control the plot, or point of view, or

degree of various properties (such as sex and violence). Several

well-publicized attempts have been realized on a theatrical level

and failed, both critically and commercially. Scores of more modest

video and animated interactive movies have been produced, but nothing

as intense and memorable as the two interactive movies made by the

Czechs.

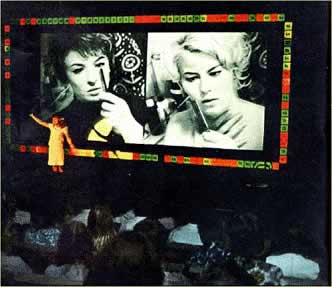

"Kino-Automat” Raduz Cincera, Director

Czech pavilion Expo '67 Montreal

The first was the "Kino-Automat" film in the Czech pavilion

at Expo '67 in Montreal, and was promoted as the world's first interactive

movie. It was film-based, and all members of the audience had a

red and a green button in front of them (the results of voting was

displayed around the screen). The movie itself was a dark comedy

about a man who believes he was responsible for his apartment building

burning down, and is structured as a series of flashbacks leading

up to the fire. After each scene the film would stop and a live

performer would walk onto the stage and ask the audience to vote.

Immediately, as if by magic, the voted scene was played.

How did they do it? Deceipt, of sorts. The branching structure wasn't

tree-like, doubling the number of scenes needed at each choice,

but rather always remained only two. They did this by carefully

crafting a story such that no matter which of the two options were

chosen, it would end up back at the same next choice. The vote was

executed by the projectionist switching one lens cap between the

two synchronized projectors. The artfulness, ultimately, was not

in the interaction but in the illusion of interaction. The film's

director, Raduz Cincera, made it as a satire of democracy, where

everyone votes but it doesn't make any difference.

The second Czech piece was called "Cinelabyrinth," promoted

as "the world's first labyrinth-style Cinematic System,"

made 23 years later for the Gas Pavillion at Expo '90 in Osaka (and

directed, amazingly, also by Raduz Cincera). Everyone began in a

single large theater sitting on the floor. At the front on each

side of the screen was a door. After the first scene was played

out, the audience was asked to chose one of two options by walking

through one of the two doors. The story was an ecology yarn about

kids trying to save a grand old tree from greedy developers. After

seeing several scenes and making several choices, enough to totally

lose one's sense of direction inside the pavillion, one watches

the final scene, where the children successfully save the tree.

ŌCinelabyrinth” Raduz Cincera, Film Director

Gas pavilion Expo '90 Osaka

At the moment when the kids shout "we did it!" the screen

in front raises up to reveal a full-size replica of the tree used

in the film. Simultaneously, three other screens on the other three

sides of the tree rise up, revealing four theaters with everyone

who began in the first room, now all facing each other. The gag

was that no matter which options were chosen, the kids successfully

saved the tree. It was as manipulative as the first Czech piece

made 23 years earlier, but this time they made it transparent. The

effect of realizing everyone "won" and now were all in

the same room together was really very powerful.

Another of the four most personally moving interactive art experiences

is Alan Lomax's "Global Jukebox" project. Alan is an 82

year old ethnomusicologist who has spent sixty years collecting

thousands of recordings of song and dance from every culture on

the planet. Moreover, he and his colleagues at Columbia University

spent twenty years (1962-82) developing a scheme to codify song

and dance, breaking each down to several dozen parameters. These

data, when cross-correlated with itself, and when cross-correlated

with other ethnographic databases of general culture, strongly suggests

that the performing arts around the world are all closely related,

and is the most robust and accurate carrier of cultural traits.

Global Jukebox Project Alan Lomax, Director

Association for Cultural Equity Hunter College New York

For example, based purely on factor analysis, Lomax has shown statistical

significance for how the traditional music of Georgian Russia is

similar to (and may be a descendent from) that of Central Africa,

and how the music of Patagonia is similar to that of the Inuit .

And how dances with strong lateral knee movement correlate with

cultures with a tradition of pottery (and potter's wheels), and

how dances with narrow heel-to-toe movements correlate with societies

whose main crop is planted in narrow rows (like rice). And how songstyles

with large amounts of rasp in the male voice correlates with societies

who raise boys to be independent rather than team players. And ones

with a high degree of tonal blend (sounding as one) correlates with

societies where women account for most of the food production. The

list goes on. It's strong, romantic, arguable stuff.

These data, along with audio and video clips of song and dance styles,

make up the Global Jukebox. You can start with a map of the world,

point to a spot, hear songstyles and see danceforms from that region,

and begin a query about how it all relates with other cultures.

Most everyone who first engages with it begins with their own roots.

It becomes a personal investigation, toggling between intellect

and emotion - and in the end synthesizing them.

Strictly speaking, the Global Jukebox is not interactive art as

much as an interactive delivery system about art. Alan's group,

the Association for Cultural Equity (relocated at Hunter College),

has worked on the current system for more than ten years. It's a

massive project and still not complete (particularly in terms of

interface). Perhaps the system itself will be considered interactive

art when it's finally completed.

The fourth and final favorite interactive art piece didn't use a

computer. It was installed at the 1980 New York Avant Garde Festival,

on the roof of the massive Cunard Terminal where the festival was

being held. It consisted of a long wide plank of wood, a box of

pencils (the standard orange kind with little pink erasers on the

ends), and several hammers. That was it.

I literally stumbled over it as it was being set up, and kept an

eye on it much of the day. The artist set the plank and the hammers

down on the floor, took out a knife and sharpened the pencils, and

left. Visitors would walk by, look at the assemblage, and, more

often than not, kneel down and try to hammer a sharpened pencil

into the plank. It was difficult (mainly due to those damn erasers!).

It was funny. And every action left a mark on the plank, successful

or not.

The artist was anonymous (although I recall he said he was Australian).

Throughout the day he stopped by regularly to sharpen the pencils,

now getting smaller and smaller. Then, at the end of the day, he

put the pencils and hammer away in his pack, heaved onto his shoulder

the plank (which now had several dozen pencils sticking out of it

and hundreds of marks), and left.

Of course I really don't believe interactive art is a bad idea.

And twenty years is not a long time for a new genre to fully evolve.

I have seen a lot of good stuff, some of which may yet be recognized

as masterpieces. The ultimate test of good art is the test of time.

Also, "interactive art" is a title currently placed upon

an aggregate of artforms. Perhaps these closer resemble the inventions

presented in the twenty years before cinema rather than after -

a hodgepodge of novelties. Transition media.

At the very least, these four examples intend to suggest a much

broader conceptual space for interactive art. Most of what's been

done so far cluster around a few tiny parcels. Spreading out may

be a good idea. Odds are the territory is much much bigger than

we currently imagine. |

|