Presence

journal

special issue on Projection

MIT Press

14.5, October 2005

Two Unusual Projection Spaces

Michael Naimark

Abstract

Two immersive projection enviroments, both unconventional,

both exploring different methods of 3D and panoramic imaging,

and both produced as art installations, are described. Displacements

(1980-1984) re-created an interior living space using a

panoramic motion picture method and relief projection. Be

Now Here (1995-1997) re-created outdoor public plazas using

a panoramic motion picture method, stereopsis, and 4 channel

sound. Both installations were unusual, in that no intentions

existed for anything more general or useful than the installations

themselves as individual artworks.

1. Background

In 1977, I began to wonder why movie cameras move and movie

projectors do not. As a graduate student at MIT's art center,

the Center for Advanced Visual Studies, and like many young

artists, old media was to be questioned and new media was

to be explored. Cinematic forms in particular, ossified

by a giant industry, were ripe for challenge and “expansion,”

and a lively community of proto-media artists was pushing

the boundaries (Youngblood, 1970). Across the street at

MIT’s Architecture Machine Group, for example, a prototype

videodisc player was on its way, and excitement was building

around using this new device for experiments with interactivity.

So it was not unnatural to question such basic tenets as

why movie cameras move and movie projectors do not.

The cheapest, fastest experiment was to mount a super-8

movie camera on a slowly rotating motorized tripod and shoot.

The camera filmed at 18 frames per second (fps) on a small

synchronous motor with a fixed rate of 1 revolution per

second (rpm). Several different focal lengths were used.

After filming, the film was loaded into a small film loop

projector popular in classrooms at the time, and placed

on top of a simple wooden turntable built around the same

1 rpm motor. One of the filmed focal lengths was within

the range of the projector’s zoom lens. (Curiously,

camera lens focal lengths are measured in millimeters and

projector lenses in inches.) The focal length was roughly

matched and the contraption was placed in the center of

a square white room.

With the projector on and the turntable off, the rectangular

movie frame appeared in the center of one of the walls,

projecting a more-or-less conventional panning shot of the

Boston skyline. When the turntable was switched on, something

magical appeared to occur. As the movie frame physically

moved across the walls, the images inside the frame stayed

put, i.e., images of stationary objects such as buildings,

trees, etc., appeared locked in place with respect to the

physical walls. One could, for example, walk up to the image

of the Hancock Building and put one's finger on the image,

and as the frame moved across, the image stayed on the finger.

This effect, a spatial correspondence between the

record space and the playback space, requires that the angular

movements, frame rates, and focal lengths match. Over the

next two years a more elaborate contraption was built to

record the pan and tilt movements of the camera (via a gimbaled

mirror), to drive the pan and tilt movements of the projected

image (Naimark, 1984). I explored this new medium in terms

of form and content and hoped it would be a useful new invention.

The eventual conclusion was: New? Yes. Useful? Not particularly.

These were the days before affordable video projection,

before real-time 3D computer models, and when tracking devices

such as the ones made by Polhemus were wound by hand and

cost $75,000 each. I finally decided that making an artistic

statement was more appropriate than making an impractical

invention.

2. Displacements (1980-1984)

Another form of alternative media I was concurrently exploring

was what is sometimes called relief projection, where an

image is projected on a screen whose shape is the same as

the image. A grotesque but amusing example at the time involved

projecting a movie close-up of a human eye onto a dome-shaped

screen. But the Architecture Machine Group had an interest

in "Transmission of Presence" at that time, and

its Director, Nicholas Negroponte, and I flew down to Orlando

to look at the famous "Talking Head" in Disney

World's Haunted Mansion. A movie of a woman's talking face

was projected onto a mannequin head in such a way that the

eyes, nose, and lips line up. Our hosts at Disney World

allowed us to view it for an extended period from behind

a nearby security curtain. It was clear that as the woman

spoke, the image of her moving lips would mis-register from

the mask-shaped screen, but to most everyone viewing it

briefly from their dark-ride car, this anomaly went unnoticed.

Most people seemed convinced that they had just seen a full

color, moving hologram (which, of course, is nonsense).

Back at "ArcMac," a more elaborate version was

built, whereby the filmed subject’s head movement

could be recorded along with image and sound. Our subject,

Professor Roy Lamson, was filmed using a super-8 sound film

camera and a ($75,000) Polhemus device secured to the back

of his head. A translucent mask of Lamson’s face was

fabricated and mounted in a pan-tilt gimbal (if the truth

be known, the same one built for my projection experiments,

collecting dust). The film was rear-projected onto the face-shaped

mask, which moved in sync with the image. The "Moving

Talking Head," even with the obvious mis-registration

due to the physical motion and filmed movement, was a popular

demo at the time (Negroponte, 1981).

An opportunity to combine relief projection with a simplified

"moving movie" arose for an art exhibition at

the Aspen Center for the Arts called “Beyond Object”

in 1980. The idea was to set up a typical Americana-style

living room on-site, then to film with a motion picture

camera on a slowly rotating turntable from the center of

the space. After filming, a matched projector would replace

the camera on the same turntable and the entire contents

of the room would be secured in place and spray-painted

white, to act as its own projection screen.

A kitschy living room was composed, mostly from thrift shop

finds, including a sofa, easy chair, several tables with

ashtrays and junk food, wall hangings, etc., all situated

around a working television set. Everything was placed against

three walls, and the fourth wall was left blank.

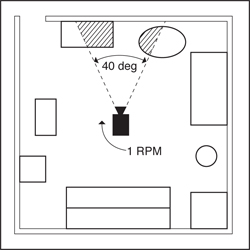

The hardware consisted of a 16mm motion picture camera crystal

synchronized to record at 24 fps, a custom-built 1 rpm turntable,

and a 16mm loop projector with a 24 fps synchronous motor.

The camera and projector had near-matching wide-angle lenses

(12.5 mm and 1/2 inch respectively) with an approximately

40-degree horizontal fields of view (FOV).

Figure 1: Schematic of camera and projection system.

Figure 2: Spray-painting everything white to become projection

screens.

The installation, obediently entitled "Moving Movie,"

was almost entirely motionless, insofar as the rotating

movie projector simply projected rotating imagery of the

stationary furniture that occupied three of the four walls.

With the direct comparison of subject and image, artifacts

became amplified. For example, the frame rate of 24 fps

was obvious. (Less obvious but noticeable to a careful eye

was that the camera used a single-bladed shutter while the

projector used a twin-bladed shutter.) Focus was an issue,

since the depth of field of the relief projection exceeded

the small depth of field designed into most projectors.

If the rotational synchronization was off by even a single

frame, the mis-registration was obvious. Still, the overall

effect appeared successful.

In what felt like a total violation of the concept, a performer

walked along the fourth blank wall. Though she added some

motion, she appeared simply as a flat projection in an otherwise

3D projection environment.

A similar installation was produced the following year,

with an intention, albeit apprehensive of the "distortional"

effects, to integrate live performers (especially knowing

that they could not be painted white!). This installation,

with another general title, "Movie Room," also

had one blank wall, on which three performers made such

actions as spray-painting graffiti as the camera panned

by. One insisted on sitting on the sofa during filming.

Another snapped a Polaroid picture and stuck it on the blank

wall during filming. I decided, after a great deal of "art

anxiety," to keep the Polaroid picture unpainted. In

the end, I was indebted to the performers. The graffiti

action was striking but safe. The performer on the sofa

appeared nicely ghost-like on top of the "very real"

looking sofa. And the image of the performer holding the

image of the Polaroid, walking toward the actual Polaroid,

and placing it there - witnessing the moment where the image

and object became one - was spine-tingling.

This anomaly was integrated into the third installation,

with little concern about violating the formalism of 3D

representation. Another living room was installed, this

time along all four walls. Lots of movable props were included:

sweaters to take off, a purse, a globe to spin, junk food

on the coffee table. Two performers were carefully scripted

to move things around during filming. Ten different rotations

were filmed. This installation remained a commentary on

the passivity of our old media, challenging them with the

rotating and relief projection, but it was equally about

the anomalies, the displacements. The piece, entitled "Displacements,"

was exhibited in 1984 at the San Francisco Museum of Modern

Art and was final.

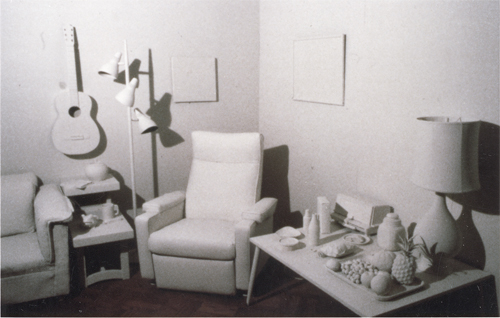

Figures 3, 4, 5: View of Displacements during filming, after

being painted white, and with final projection.

3. Be Now Here (1995-1997)

Eleven years later, I was unknowingly nearing the end of

a two-decade investigation exploring how new media technologies

could expand the range of "place representation."

This investigation followed two parallel tracks: one based

on panoramic or angular "look around," such as

the “moving movie” work above; and the other

based on lateral "move around," such as what came

to be called "moviemaps." In both cases, the work

had increasingly explored filming outdoor landscapes for

immersive, sometimes interactive, art installations. I had

just finished an immersive moviemap installation filmed

with side-by-side cameras for stereopsis, the first-ever

stereoscopic moviemap (Naimark, 1997). It seemed as if the

last unchecked box of an invisible matrix was to make a

stereoscopic motion picture panorama filmed in outdoor landscapes.

I had also become increasingly politicized regarding content.

The innocence and safety of filming along the Charles River

across the street from MIT faded as I filmed more and more

in other places, particularly in other countries. It became

increasingly clear that whoever controls representation,

controls everything (Naimark, 1998).

In 1995, this final project took shape with the support

of Interval Research Corporation and the cooperation of

the UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Interval Research encouraged

arts and media projects, particularly if the results could

stimulate and cross-pollinate other research activities

there. The UNESCO World Heritage Centre, in Paris, designates

sites around the world with extraordinary cultural or natural

value, including a lesser-known list of World Heritage site

"In Danger." At the time, of the 440 designated

World Heritage sites, 17 had been further designated "In

Danger," and four of the 17 were cities: Jerusalem;

Dubrovnik, Croatia; Timbuktu, Mali; and Angkor, Cambodia.

Both spectacular and troubling, these cities would become

the subject of this new project.

The idea was to re-create simply "being" in these

four cities, in public plazas that best represents them.

Specifically, the plan was to work with local collaborators

to find the most representative public plaza in each location,

then to select one spot in each of these plazas from which

to film. The goal was to allow "3D lookaround"

via stereoscopic panoramas.

Stereoscopic panoramas present a curious dilemma. Panoramic

images are two-dimensional by nature, representing a single

point of view. Two side-by-side panoramic images can be

recorded for stereopsis, but the degree of disparity will

change depending on the viewpoint, dropping to zero when

the viewpoint is in line with the two cameras. Disparity

can be kept constant by rotating the cameras about each

other, but then the panoramic images no longer represent

single viewpoints (e.g., circles may become ellipses). A

small but lively community can be found on the Web making

stereoscopic QuickTime VR panoramas by tiling together images

using conventional cameras and living with the disparity

or viewpoint artifacts. These images are usually viewed

in stereo using red/blue anaglyph glasses. Several novel

attempts have been made to build single stereo-panoramic

cameras (e.g., Peleg, 1999).

Two motion picture cameras would be used to record moving

imagery, with the cameras side-by-side for stereo, rotating

on a 1 rpm motorized tripod. The movie could appear to rotate

around the viewers, like the earlier "moving movie"

projects, revealing a panorama over time. John Woodfill,

a computer vision colleague at Interval, proposed rotating

both cameras around the nodal point of one of the cameras.

Rotating about the nodal point of, say, the left camera

would result in a perfect single-viewpoint representation

that could be used for further experimentation. One might

speculate that looking at a stereoscopic panning movie where

one eye sees no disparity and the other eye sees all the

disparity would be noticeable. But one could counter-speculate

that it's possible to sit on a rotating stool with one eye

directly over the axis of rotation and conclude that there's

nothing special about it.

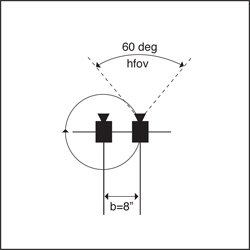

Figure 6: Schematic of Be Now Here camera system.

The camera system was based on two 35mm motion picture cameras,

the kind used in professional movie production. These cameras

have higher spatial resolution and dynamic range than conventional

video cameras and are far more robust under extreme and

remote environments. The cameras were synchronized to run

in phase at 60 fps (rather than the standard 24 fps) and

had variable shutters that could close down to 30 degrees,

resulting in an effective shutter speed of 1/720 second,

fast enough to freeze most everything. High quality Zeiss

lenses were used with very wide-angle 60-degree horizontal

FOVs. Partly for practical reasons, the cameras had to be

mounted with the lenses separated by 8 inches, resulting

in a "hyper-stereo" effect due to the exaggerated

interocular distance. The camera system was, by choice,

approximately 7 feet from the ground. The result would be

a slowly rotating stereoscopic movie with high spatial and

temporal resolutions, an immersively wide FOV, and a viewpoint

resembling a very tall person with a very big head.

The entire system, including cases, weighed 500 pounds but

was built to travel. All production took place in one rather

insane month flying around the world (Naimark, 1995). A

digital audio recorder with a shotgun microphone was used

to collect sounds at each site for later mixing into 4 channel

rotating sound. Enough stock to film 5 panoramas (10 reels

of 400' film) was taken to each site. Miraculously, production

stayed on schedule and everything came out. The film footage

was transferred to videotape, edited, and mastered onto

laserdiscs.

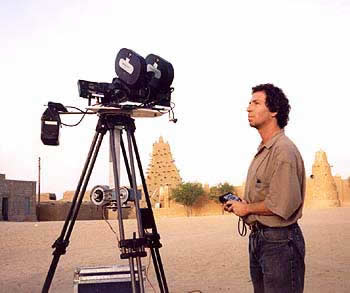

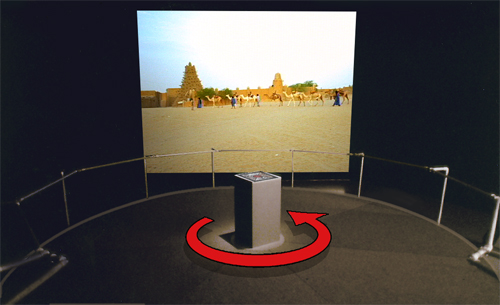

Figure 7: Camera system for Be Now Here during production

in Timbuktu, Mali

For playback, the ideal solution may have been to rotate

the stereoscopic image around the viewers like the previous

moving movies. But in order for the image to appear orthoscopically

correct, the rotating projectors would require 60-degree

horizontal FOVs, far too wide for all but the most exotic

video projectors. The solution, we surmised, was to rotate

the viewers instead. Consider: if the floor on which the

viewers stand rotated in sync with the panning image, and

if the speed was not too fast to be consciously detected

by our vestibular system, and if the rest of the space was

dark enough to minimize other frames of reference, a strong

visceral illusion would result. This illusion would be similar

to the feeling we’ve all experienced when our train

sitting in the station seems to be moving when the adjacent

train pulls out.

The installation, called "Be Now Here," initially

employed a 16 foot diameter 1 rpm rotating floor, a 12 by

16 foot front projection screen capable of maintaining polarity,

four channel surround audio, and a custom-designed input

pedestal allowing viewers to interactively change location

and time of day. The input pedestal was situated in the

center of the floor, from which viewpoint the screen appeared

orthoscopically correct. Two video projectors showed material

from two synchronized, computer-controlled laserdisc players,

and the viewers wore inexpensive polarizing glasses.

Figure 8: Installation view of Be Now Here.

The overall effect worked, but a small percentage of viewers

complained of vestibular problems, dizziness, from the rotation.

After two public exhibitions, informal tests were made back

at Interval slowing down the floor and motion picture together

to one half and one quarter of the original speed. At half

speed, the "moving train illusion" remained strong

but the dizziness disappeared for most everyone tested,

and at quarter speed, the illusion largely disappeared (Naimark,

1997b). The video was re-edited for half speed and the sound

was re-mixed, resulting in slow motion imagery with real

time surround sound. Incredibly, very few viewers were aware

that the footage was slowed down.

It was also felt that the more visible cues of the actual

(non-rotating) space could be masked, the more effective

the illusion would be. The entire installation was enclosed

with a black cylindrical wall, using a simple cage structure

from which back drapery could be suspended. This modification

required changing from a front screen to a rear screen,

and fortunately for us, an inexpensive, flexible rear screen

material that maintains polarity had recently become available.

The original 12 by 16 foot front screen was replaced by

a 9 by 12 foot rear screen and placed correspondingly closer

to keep the FOV orthoscopically correct, approximately 12

feet from the center of the floor. Now viewers could come

as close as 4 feet to the screen. Surprisingly, few viewers

seemed bothered, or even aware, that their eyes were accommodating

much closer than what would be consistent with the landscape

imagery, and the feeling of immersion remained.

Interval was granted a patent for the Be Now Here immersive

illusion in 1997 (US 5,601,353) and the footage was "mined"

for other research applications. For example, Paul Debevec,

then an Interval intern from UC Berkeley, filmed squares

and cubes covered with checkerboard material, which he and

several other computer vision researchers used to explore

panoramic tiling, background subtraction, and depth from

stereo. Romy Achituv, another Interval intern from NYU,

made a screen-based interactive version of Be Now Here that

combined different times and places into a single panorama

(Achituv, 2000). Students at MIT and UNC also used the footage

for various experiments. Most recently, the footage was

used to simulate what "VR Webcams" might be like

(Naimark, 2002).

Be Now Here continued to exhibit in venues including technical

(Siggraph, 1996, and the Tech Museum of Innovation, 1998),

cinematic (Rotterdam and San Francisco Film Festivals; 1998,

2001), and art (Art at the Anchorage NY, 1997 and Kiasma

Museum of Contemporary Art Helsinki, 2003). But, happily,

it is not without company: a lively community of media artists

continues to push the boundaries of cinematic forms in a

still-ossified giant industry, ripe as ever for challenge

and expansion (Shaw and Weibel, 2003).

4. Discussion

Displacements and Be Now Here share several common features

but also some major differences. Both were attempts to make

immersive virtual environments, particularly using motion

picture media with 3D and panoramic components. Both were

exploring radically different ways of experiencing cinema,

and both had little concern for generalization beyond the

art installations themselves.

The most top-level observation is that the eye is incredibly

difficult to fool. Both installations attempt to make mediated

experiences "just like being there." Both installations

may have looked "more real" than conventional

cinema or television due to higher resolution, proper orthoscopy,

panoramic immersion, and stereopsis, but neither came close

to passing the media equivalent of the Turing Test: "indistinguishable

from the unmediated." (In fact, no visual media, including

3D Imax, can.) This is a sobering lesson for anyone working

in VR.

The level of transparency between the two installations,

i.e., the degree by which the process is visible, was nearly

opposite. Displacements was completely transparent. It was

obvious that the only way to have made it was to have filmed

the room, then painted everything white, then projected

the original film back onto everything. Even children delighted

in reverse-engineering this process. Be Now Here, on the

other hand, was completely opaque. Viewers put on polarized

glasses, then stepped into a completely black room except

for the screen (which, with the glasses, looked more like

a window). They often didn’t realize the floor was

rotating (why would they?). In contrast to the children’s

delight learning the process of Displacements, viewers of

Be Now Here were often confused and sometimes disturbed.

Many reported that the actual feeling of "being there"

was very strong but couldn’t understand why.

Intentionally or not, both installations exploited novelty.

Just as when audiences of the Lumiere’s film of an

oncoming train ducked in 1895, seeing these unusual forms

for the first time caught viewers by surprise. Perhaps if

we were all accustomed to rotating projectors, room-size

relief screens, stereopsis, or rotating floors, the novelty

value of Displacements and Be Now Here would be thin.

But we’re not, and exploring such unusual projection

spaces is potentially boundless, given the range of possibility

that new media technologies afford, with a little unfettered

imagination. To explore these possibilities looking for

something useful, or for a new standard, or to make a fortune,

may miss the richest experiences. These may come under the

province of art, even if sometimes by default.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges that Displacements received

support from the MIT Council for the Arts and the National

Endowment for the Arts, and that Be Now Here received support

from Interval Research Corporation, Palo Alto, and the UNESCO

World Heritage Centre, Paris.

References

Achituv, R. (2000). http://www.gavaligai.com/main/sub/interactive/BNHI/BNHI2.html

, May 2005

Naimark M. (1984). Spatial Correspondence in Motion Picture

Display. SPIE, 462.

Naimark M. (1995). Trip Reports, (self published) http://www.naimark.net/writing/trips/bnhtrip.html

, May 2005

Naimark M. (1997). A 3D Moviemap and a 3D Panorama. SPIE,

3012.

Naimark M. (1997). What’s Wrong with this Picture:

Presence and Abstraction in the Age of Cyberspace. Consciousness

Reframed Proceedings, CAiiA, University of Wales, Newport,

Wales.

Naimark M. (1998). Place Runs Deep: Virtuality, Place, and

Indigenousness. Paper presented at the Virtual Museums Symposium,

Salzburg, Austria. See http://www.naimark.net/writing/salzberg.html

, May 2005

Negroponte, N. (1981). Media Room. Society of Information

Displays, 22 (2).

Peleg, S. and Ben-Ezra, M. (1999), Stereo Panorama with

a Single Camera, CVPR’99.

Shaw, J. and Weibel, P. (Eds.) (2003), Future Cinema: The

Cinematic Imaginary After Film, MIT Press.

Youngblood, G (1970). Expanded Cinema. Dutton.

|