Consciousness Reframed: Art and Consciousness

in the Post-biological Era

Proceedings of the 1st International Conference of the

Centre for Advanced Inquiry in the Interactive Arts

University of Wales, Newport, 1997

Ascott, R. ed. 1997. Newport: University of Wales College

ISBN: 1 899274 03 0

What's Wrong with this Picture?

Presence and Abstraction in the Age

of Cyberspace1

Michael Naimark

A great deal of attention has been

given over the past two decades to technologies for making audiovisual

representations appear "more real." Photorealism in computer graphics,

binaural sound, high definition television, interactivity, and (as

the name implies) virtual reality are such areas. This issue of

"realness" or "presence" has split the arts community into two camps:

those who care and those who don't. Historical examples of this

split will be discussed, including at the 1900 Paris Exposition,

in Abel Gance's Napoleon (1927), and at the Macy Conferences on

Cybernetics (1947-53). Attempts at syntheses of these views will

be suggested.

KEYWORDS: presence, abstraction, virtual environments

PART I - The Problem

Art "versus" Tech?

It's not wholly inaccurate to place "abstraction" and

"presence" as end-points along a single axis depicting

representation, which loosely translates into "less real"

and "more real." Abstraction may also be tied heavily

to "metaphor," while presence may be tied to "verisimilitude."

An equally tempting correlation, one might observe, exists between

abstraction and "art," and presence and "technology."

For example, increasing the resolution of an electronic image or

reducing the latency in an interactive system is generally viewed

as a technological enhancement, while decreasing resolution or making

a seemingly non-causal interface is considered poetic or artful.

For many practitioners of art and technology (including the author),

such a correlation feels both accurate and disturbing. Often, after

an artwork is realized, colleagues from the technological community

may say things like "this is great but wouldn't it be better

if you had more bandwidth?" while colleagues in the traditional

arts community may counter with "this is great but wouldn't

it be more poetic if you made it more abstract?" To many of

us, this apparent dichotomy is a constant source of tension, manifesting

in such questions as "can I use 8mm video instead of professional

beta format," "should I keep the noise and artifacts,"

or "will distorting the sound or image help or hinder what

I'm trying to express."

The Mixing Board Analogy of Representation

A simple model of the relationship between a subject and its representation

can be made by analogy to an audio mixing board - a box with an

input, and output, and rows and rows of slider controls. The analogy

is that the sliders depict all of the individual elements of representation

and that if all are turned up to their maximum, that the representation

will be indistinguishable from its subject. For example, if the

representation is visual, the sliders may depict elements such as

spatial resolution, temporal resolution, dynamic range, color fidelity,

degree of orthoscopy, etc.

This model assumes these elements are known (or at least knowable).

The author has written several papers attempting to taxonomize these

"elements of realspace imaging" [see Naimark (1991a, 1991b,

1991c)].

The relevant issue here is not whether this mixing board analogy

is accurate, but whether or not it's relevant to the arts. And here

is where two camps can be observed.

One camp seems to scream "turn all the sliders up to 10!"

This can be seen at technology-based exhibitions such as Siggraph

and has been the battle-cry in many VR circles. Sutherland (1965)

said it first, if not best: "The screen is a window through

which one sees a virtual world. The challenge is to make that world

look real, act real, sound real, feel real." An implicit assumption

here is that the world is sensed the same by all people and what

seems real to me will seem real to you, a very deep assumption about

human cognition and consciousness.

The other camp says, simply put: "Who cares!" These tend

to be artists working in traditional media, such as painters and

poets. An artist friend of the author whose medium is 16mm film

(and who despises video and computers) once said that he likes his

medium for all the reasons folks like me don't: all of the exploration

has already been done and he can simply use it.

A Case Study: "Be Now Here"

This apparent dichotomy, between presence and abstraction in the

arts, can be seen in the evolution of a recent project by the author

called "Be Now Here (Welcome to the Neighborhood)." "Be

Now Here" is an immersive virtual environment about public

plazas in endangered areas, whose intention is to express a strong

visceral sense of place. The installation consists of a large stereoscopic

video screen (the audience wears inexpensive polarized glasses),

four-channel surround sound, a simple input device, and a 16-foot

diameter rotating viewing platform on which the audience stands,

which rotates in sync with the panoramic image and sound [see Naimark

(1995)].

The imagery was filmed with a stereoscopic pair of cameras on a

custom-built tripod which constantly rotated at a rate of once per

minute (1 rpm). The rotating floor also rotated at 1 rpm. The effect,

of being in a dark space viewing a large screen, was a strong sense

that the screen was rotating rather than the floor. This illusion

is similar to the feeling of sitting in a train at a station when

the adjacent train pulls out.

But after two public exhibitions, it became clear that too many

people were complaining of mild dizziness from rotating at 1 rpm.

Several informal experiments were conducted back at the lab. The

turntable and video were slowed down in sync to 1/2 rpm and to 1/4

rpm. Most observers reported a drastic decrease of dizziness at

1/2 rpm and little further change at 1/4 rpm. They also reported

little decrease in the effectiveness of the "moving train"

illusion at 1/2 rpm but a marked decrease at 1/4 rpm. The conclusion

was to slow down the turntable and video to 1/2 rpm.

Since the imagery was pre-recorded, slowing it down to half-speed

meant the people in the video would appear moving in slow-motion.

Changing the imagery from real time to half-speed is making it "less

real" and "more abstract." From the point of view

of the one-dimensional model of presence and abstraction, such a

change would move "Be Now Here" more toward art and away

from technology in its sensibility. (Indeed, a colleague with whom

I work, a computer scientist, gave me a look of shock when I described

the change and said "but Michael, the people in the video will

be moving in slow motion!" as if I was doing something

terribly wrong.)

That Be Now Here #2 (1/2 rpm) would satisfy the technologists less

and the artists more than Be Now Here #1 (1 rpm) proved indeed to

be both accurate and disturbing. The tension between abstraction,

metaphor, and art on one side and presence, verisimilitude, and

technology on the other is not new. Perhaps looking at past examples

of this tension would add insight.

PART II - Three Historical Moments

1 - 1900 Paris Exposition: Did Cezanne know the Lumiere brothers?

Paris at the turn of the last siècle was a lively

place for artists working both with abstraction and presence. The

abstract movement of Impressionism, already several decades old,

was by 1900 known as "post-Impressionism" and in a state

of maturity. Cezanne ruled (ask Picasso) and had moved out of the

studio into the field, from still lifes to landscapes. His painting

entitled "Turning Road at Montgeroult" (1899) was typical

of his style then: soft blurry edges, large swatches, and his bold

and complex use of color made it crystal clear that photorealism

was not a high priority.

P. Cezanne Turning Road at Montgeroult 1899

Meanwhile, cinema was in its early infancy, five years old to be

precise, and Paris was a hotbed of activity. The Lumiere brothers

publicly opened the first projected film theater in late 1895, and

cinema became such an instant hit that early film posters depicted

nothing but a mob of people trying to get inside the film theater

[see Capitaine (1993)]. Cinema's attraction was that it "looked

real."

|

|

| 1895 |

1896 |

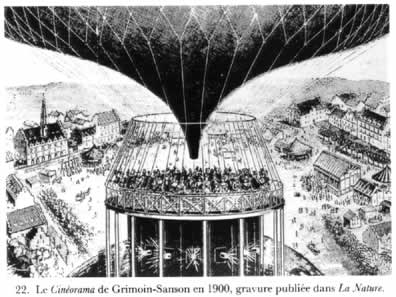

Paris became a particular focus of worldwide attention when it opened

its doors to the world's fair in 1900, the Paris Exposition, the

largest of its kind to date. Art was exhibited alongside cinema.

But did these two communities - the mature abstractionists of post-Impressionism

and the proto-VR cinéastes - intermingle?

1900 Paris Exposition

As far as this author could determine: no. At the 1900 Paris Exposition,

cinema was well-represented as was classical art, but the Impressionists

were barely exhibited, having been co-opted by Art Nouveau,

the fashion rage of the time [see Mandell (1967)]. It seems that

the abstractionists and the cinéastes ultimately didn't

have much in common and remained in their own communities. (Asking

if Cezanne hung out with the Lumiere brothers is a little bit like

asking if Jasper Johns hangs out with Jaron Lanier. They do both live in New York.)

2 - 1927 - Abel Gance's Napoleon: VR or Collage?

In 1925, the French filmmaker Abel Gance began filming one of the

most anticipated movies in the history of film: Napoleon. Exotic

locations, casts of thousands, and (to the French) the greatest

story of heroism and the human spirit came together in what Brownlow

(1983) called "so far ahead of its time that it seemed set

to become the most famous [film] ever made."

The film premiered in April 1927 at the Paris Opéra to a

full house and ran three hours forty minutes. When it ended the

audience gave Gance a standing ovation which lasted fifteen minutes.

The most innovative achievement of Gance's Napoleon was his use

of three screens side by side to make an enormous triptych, 40 feet

wide at the Opéra. Gance filmed several scenes with three

cameras with the intention of creating a long continuous panorama.

This technique, which he called "Polyvision," was the

early predecessor of Cinerama, the popular three-screen movies of

the 1950s. The goal was heightened realism.

But during the editing process Gance made another discovery: that

by using the three projection screens to show three different images

side-by-side, an impression as powerful as his panoramas could be

made. From Brownlow (1983), Gance recalls "I realized that

here was a new alphabet of cinema. I had only to create the grammar."

In the end, Gance's Napoleon used his three screen triptych for

both panoramas and collages, and he spoke with equal passion of

both techniques. It may be noteworthy that he was initially driven

by the quest for heightened realism that lead him to heightened

abstraction.

Unfortunately, 1927 was also the same year The Jazz Singer was released

- the first "talkie" - and silent films, however epic

and innovative, became a lost art.

3 - 1947-53 - Macy Conferences on Cybernetics: Where are "YOU?"

In 1947, the Josiah Macy Foundation in New York began sponsoring

a series of conferences on communication, feedback (a new word,

coined by Norbert Wiener), and systems. The conferences were originally

called "Circular Causal and Feedback Mechanisms in Biological

and Social Systems" and had an eclectic mix of scientists and

engineers including Norbert Wiener, Claude Shannon, Warren McCulloch,

and Heinz von Foerster, but also anthropologists Margaret Mead and

Gregory Bateson. In 1948, Wiener published his book Cybernetics (another word he coined), and shortly thereafter everyone at the

conferences agreed to change the name to the "Macy Conferences

on Cybernetics." In a very real sense, the field of cybernetics

was born at these conferences.

Participants of the Tenth Conference on Cybernetics,

April 22-24, 1953, Princeton, N.J. Sponsored by the Josiah Macy,

Jr., Foundation. 1st row: T.C. Schneirla, Y. Bar-Hillel, Margaret

Mead, Warren S. McCulloch, Jan Droogleever-Fortuyn, Yuen Ren Chao,

W. Grey-Walter, Vahe E. Amassian. 2nd row: Leonard J. Savage, Janet

Freed Lynch, Gerhardt von Bonin, Lawrence S. Kubie, Lawrence K.

Frank, Henry Quastler, Donald G. Marquis, Heinrich Kluver, F.S.C.

Northrop. 3rd row: Peggy Kubie, Henry Brosin, Gregory Bateson, Frank

Fremont-Smith, John R. Bowman, G.E. Hutchinson, Hans Lukas Teuber,

Julian H. Bigelow, Claude Shannon, Walter Pitts, Heinz von Foerster

Brand (1976) interviewed Bateson and Mead about the Macy Conferences.

One of their observations was that most of the participants ("the

engineers," as they called them) characterized a cybernetic

system as having an input, an output, and feedback but saw themselves

as "outside the box," i.e., not being part of a bigger

circuit. Wiener, Bateson, and Mead believed that everyone is ultimately

"inside the box" and that a larger feedback loop including

"you" always exists.

Stewart Brand, œFor God's Sake, Margaret,” (conversation

with Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead) The CoEvolution Quarterly,

Summer 1976

The engineers, who believed they were outside the systems they study,

and Wiener, Bateson, and Mead, who proposed no one ever is, embody

a similar dichotomy as that of presence and abstraction. At the

very least, being "outside the box" assumes a common reality

while being "inside the box" acknowledges subjectivity.

This "inside the box" view, one of self-reference, is

(arguably) one of the seed beliefs which led von Foerster to his

theory of Second Order Cybernetics and Francisco Varela and Humberto

Maturana to their theories of "autopoeisis."

But as tempting as it may be to suggest that "outside the box"

is an inferior view, "the engineers" went forth and founded

several industries, like computers and telephony. Sometimes a little

bit of distancing is a good thing, and ultimately both views may

have some value.

PART III - A New Axis

These three historical moments may suggest that, while presence

and abstraction can be one-dimensionalized in terms of mixing board

psychophysics, quality of experience is ultimately orthogonal to

it. To suggest that more or less image detail, or more or less panoramic

continuousness, or even more or less self-reference, makes a representation

better or worse collapses one too many dimensions together. The

dimension of quality - some may call this art - cannot follow simple

rules.

References

1. This paper is loosely based upon a presentation given for the

classes of Anne-Marie Duguet of Université Paris 1 and Jean-Louis

Boissier of Université Paris 8 in 1994.

2. Naimark, M. 1991. Elements of Realspace Imaging. Cupertino: Apple

Computer Technical Report.

3. Naimark, M. 1991. Elements of Realspace Imaging: a Proposed Taxonomy.

San Jose: SPIE/SPSE Electronic Imaging Proceedings, vol. 1457.

4. Naimark, M. 1991. Elements of Realspace Imaging: a Proposed Taxonomy.

Moscow: First Moscow International Workshop

on Human-Computer Interaction Proceedings.

5. Sutherland, I. 1965. The Ultimate Display. Proceedings of the

IFIP Congress Vol. 2.

6. See http://www.naimark.net/projects/benowhere.html

7. Capitaine, J-L. 1993. L Invitation au Cinématographe.

Paris: Maeght Éditeur.

8. Mandell, R. D. 1967. Paris 1900: the Great World s Fair. Toronto:

University of Toronto Press.

9. Brownlow, K. 1983. Napoleon: Abel Gance s Classic Film. New York:

Alfred A. Knopf.

10. Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation. 1949-53. Cybernetics (6th - 10th;

Vols. 1-5 not published). New York: Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation.

11. Brand, S.B. 1976. For God s Sake, Margaret: Conversation with

Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead. Sausalito: CoEvolution Quarterly

(summer 1976).

|

|